The tickle is a complex sensation; it occurs in response to touch but not unequivocally so, and it makes us laugh, although not when we perform the action ourselves. To fully understand this phenomenon, a distinction between two very different percepts is necessary.

The first, knismesis, describes a light and feathery touch, like a spider that crawls on the skin. This sensation is readily elicited on any part of the body and one can evoke it on oneself.

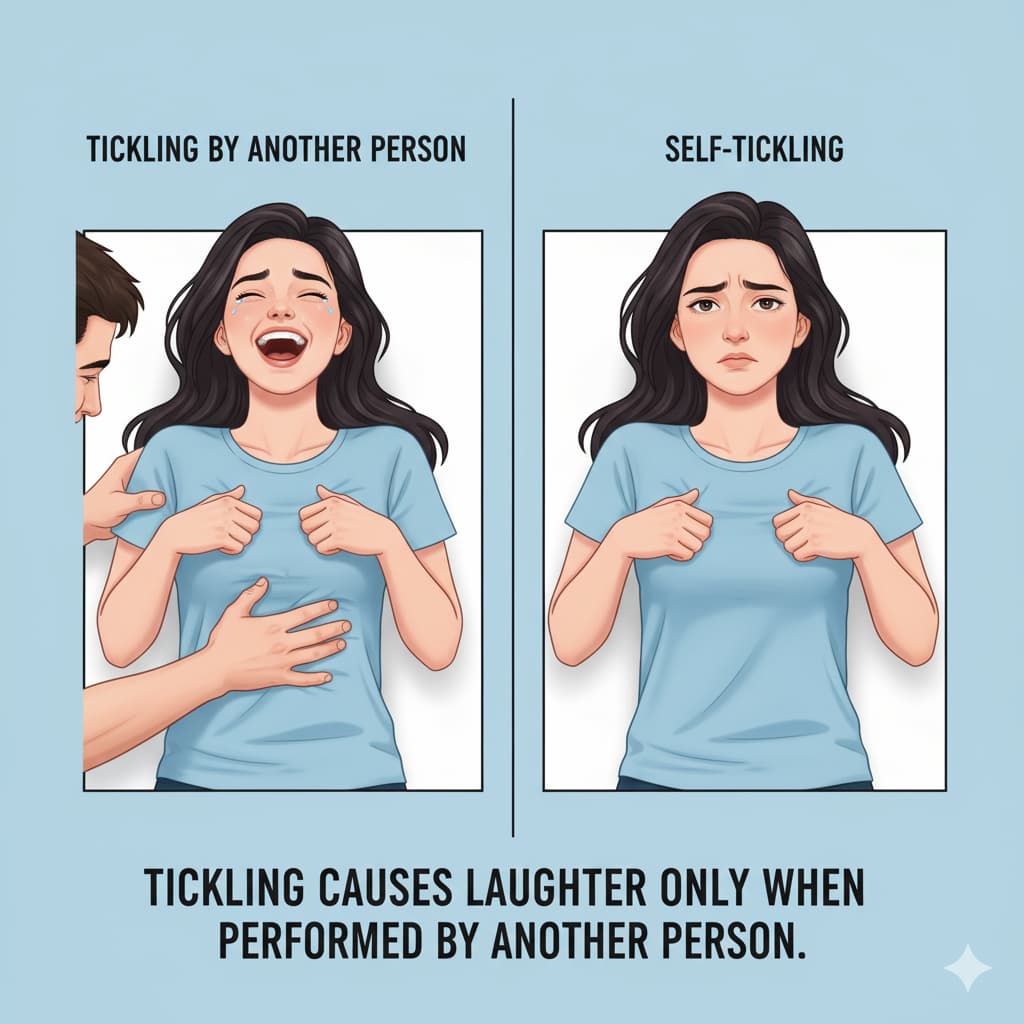

The second, gargalesis, is the reaction to heavy and rhythmic touch. It occurs only at certain body parts, depends on mood and context, and is the only form of touch that provokes laughter. This second type is almost never evocable through self-touch.

The biological origins of tickle-induced laughter are deep. Laughter has profound evolutionary roots, as many mammals, including chimpanzees and dogs, produce laughter-like vocalizations during play. Tickling serves as the closest link between human laughter and other mammalian play vocalizations. This suggests a phylogenetically conserved behavior that could date back to the last common ancestor of great apes, approximately 10 million years ago. Laughter evoked by tickling is a primitive form of vocalization that evolves during an early phase of postnatal life and appears independent of higher cortical circuits. Indeed, human infants start to laugh within weeks of birth, and even congenitally deaf individuals produce laughter with acoustic structures fundamentally similar to those of hearing individuals. These findings suggest that innate mechanisms play a key role in this vocal behavior.

The reason we feel a tickle lies in specific neural mechanisms. The functional magnetic resonance imaging study “Exploration of the neural correlates of ticklish laughter” investigated the neurological basis for this involuntary reaction. In this investigation, healthy participants experienced three conditions: 1) they were tickled on the sole of the right foot with permission to laugh, 2) they were tickled but asked to stifle laughter, and 3) they were requested to laugh voluntarily.

The results showed that tickling accompanied by involuntary laughter activated certain brain regions to a consistently greater degree. These regions included the lateral hypothalamus, the parietal operculum, the amygdala, and the right cerebellum. The present findings indicate that hypothalamic activity plays a crucial role in the evocation of ticklish laughter in healthy individuals. The hypothalamus promotes innate behavioral reactions to stimuli and sends projections to the periaqueductal gray matter (PAG), which is an important integrative center for the control of vocalization. Activation of the PAG was observed during both voluntary and involuntary laughter but not when laughter was inhibited.

The science behind the ticklish laughter

Laughter from a tickle is not just any laughter; it possesses a unique acoustic and perceptual profile that distinguishes it clearly from laughter caused by other triggers. A study that used machine learning analyzed 887 spontaneous laughs from real-life videos, where the context was coded into four types: being tickled, watching something funny, witnessing someone else’s misfortune, and hearing a verbal joke. A machine learning classifier showed that laughs produced during tickling are acoustically distinct from laughs triggered by other events. The most differentiating acoustic features included the rate of voiced segments, the amplitude variation of vocal cord vibration (known as shimmer), and loudness variability. For example, a person who is tickled produces laughs with fewer rhythmic bursts compared to laughs from other contexts.

These acoustic differences have a perceptual counterpart. A listening experiment confirmed that human listeners can accurately identify tickling-induced laughter from sound alone, without any visual cues. A second listening experiment explored how people perceive these laughs. Participants evaluated laughter on several perceptual features, including arousal, positivity, control, familiarity, and physical contact. The results showed that laughs from tickling contexts were perceived as higher in arousal and significantly less controlled than other laughs. Listeners also thought tickling laughs were more likely to occur in situations that involved more physical contact and greater familiarity between the people involved. Interestingly, perceived positivity did not differ between the laughter types. The heightened arousal and reduced vocal control suggest an automatic response tied directly to the physical act of the tickle, beyond its emotional valence. This might help explain why, despite the laughter, some individuals find the experience unpleasant; individual ticklishness may depend on the activation of the limbic system and its fight-or-flight network.

Another scientific investigation, “The human tickle response and mechanisms of self-tickle suppression,” performed a systematic assessment of the human gargalesis response in a controlled environment. For this experiment, participants joined in pairs to ensure familiarity, which enhances the tickle response. The researchers measured facial expressions, thoracic circumference (as an indicator of breath), and vocalizations when participants were tickled on various body parts, such as the armpit, trunk, and foot. The data revealed a rapid physiological response timeline. Changes in joyous facial expressions and breathing co-emerge approximately 300 milliseconds after tickle onset. Vocalizations, the laughter itself, follow with a delay and start after an additional 200 milliseconds, at around 500 milliseconds post-touch. A remarkable conclusion from this study is that the acoustic properties of laughter tightly correlate with the subjective experience; the faster, louder, and higher-pitched participants laughed, the stronger they rated the experienced ticklishness. This suggests ticklishness may be a multisensory percept, where a person can “hear” the intensity of the sensation, not just “feel” it.

Finally, one of the most curious aspects of tickling is our inability to do it to ourselves. The same study by Proelss and colleagues investigated the mechanisms of this self-tickle suppression. They compared the response to an external tickle (allo-tickling) with a condition where the participant simultaneously self-tickled while another person also tickled them. The results showed that co-applied self-tickling reduces ticklishness ratings and delays the onset of vocalization.

The suppression is strongest when the self-produced movement results in actual tactile sensation, rather than a motion without contact. This indicates that sensory attenuation is not based just on the predictability of a self-generated action but on a broader process that inhibits temporally coincident sensory inputs. In this model, self-touch causes cortical inhibition that exceeds the excitation from the external stimulus. Thus, the diminished tickle sensation arises more from the sensory consequence of self-touch, which highlights the crucial role of tactile processing in this phenomenon.