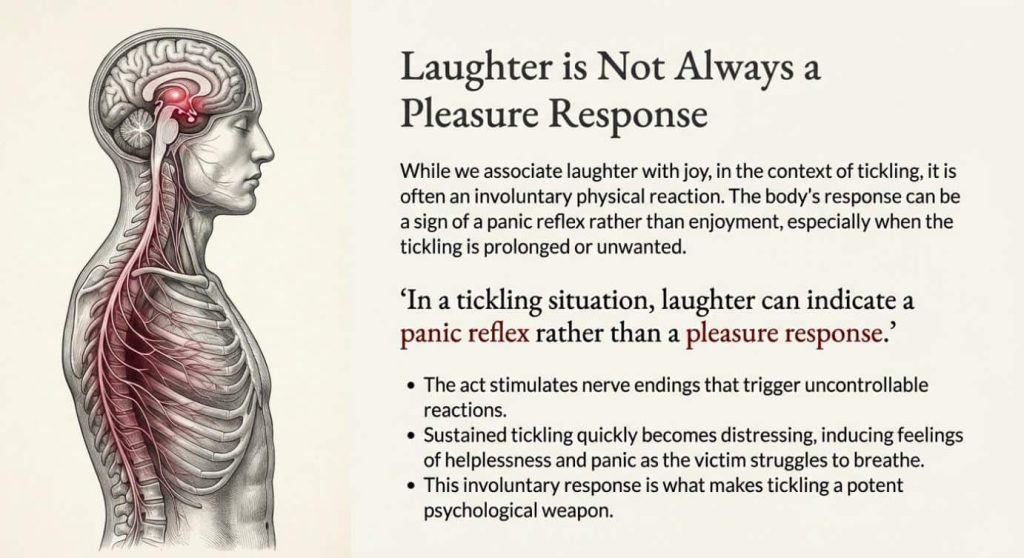

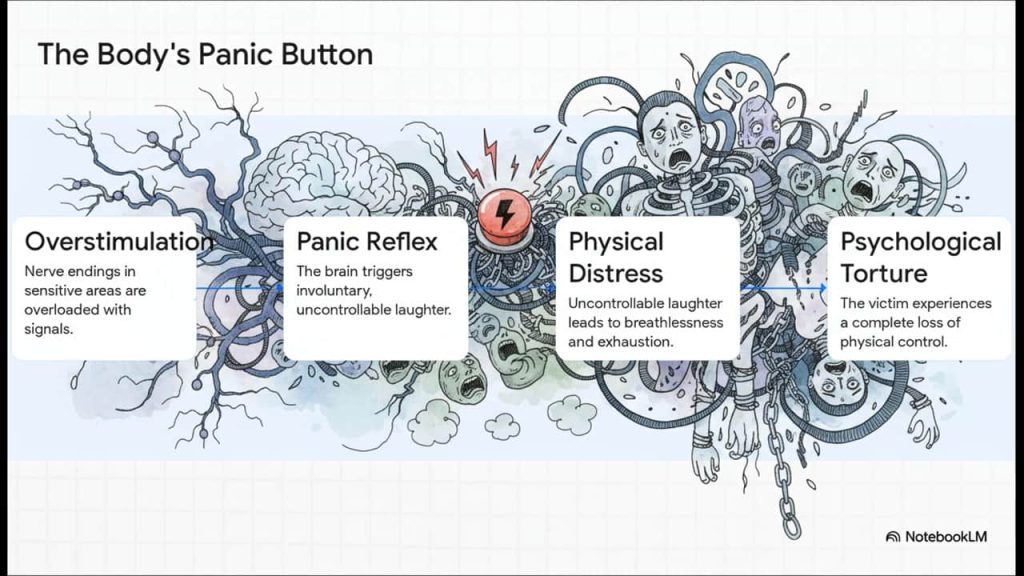

Tickle torture may sound whimsical or even humorous to modern ears, but its historical application was often far from innocent. Defined as the prolonged use of tickling to abuse, dominate, harass, humiliate, or interrogate an individual, it leverages a physiological response that the victim cannot control. While laughter is popularly perceived as an expression of joy, in the context of torture, it is often a panic reflex or an involuntary reaction to sensory overload.

The practice is particularly effective because it preys on the body’s nerve endings, which send signals to the brain that trigger uncontrollable laughter and heightened sensitivity. Over time, this sustained stimulation can lead to extreme distress, breathlessness, and physical exhaustion, transforming a seemingly harmless act into a potent weapon of coercion and control.

Contents

Why are we ticklish?

Ancient philosophers and modern scientists have offered several explanations for why human beings are ticklish, often linking the sensation to biology, evolution, and social development.

Aristotle famously posited that humans are the only creatures susceptible to tickling due to the unique fineness of their skin and their exclusive capacity for laughter,. He viewed this vulnerability as the price humans pay for having a more sophisticated and discriminating sense of touch compared to other animals. Later, the philosopher René Descartes suggested that tickling is a specific form of nervous stimulation where the movement of nerve fibers excites the body in a manner that closely resembles the experience of pain,.

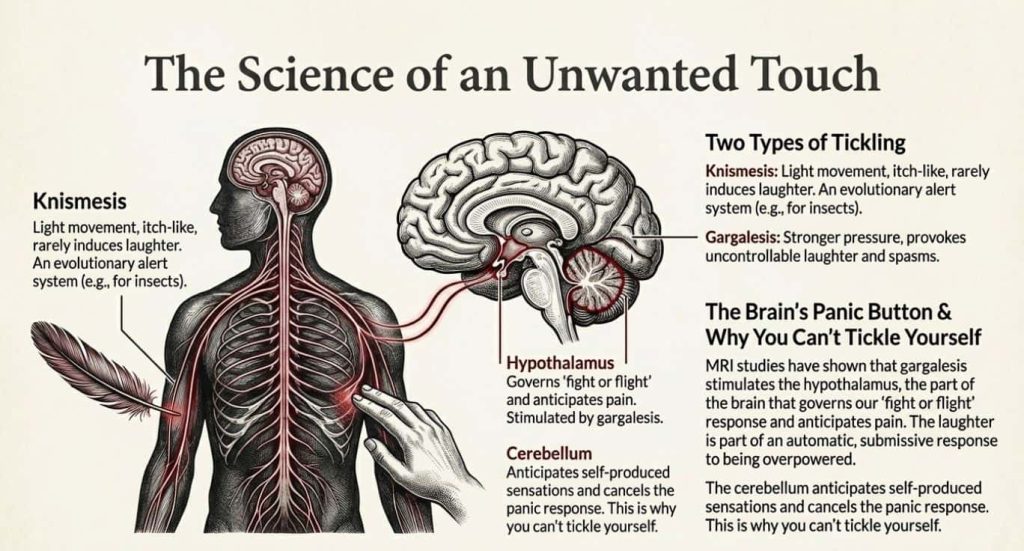

On a biological level, tickling preys on the body’s involuntary reactions by sending signals from nerve endings to the brain, which often triggers a panic reflex rather than a response of genuine pleasure. Researchers distinguish between two types of this sensation: knismesis, a light movement across the skin similar to a feather, and gargalesis, which is produced by heavier pressure or poking.

From an evolutionary perspective, ticklishness may have developed as a prehistoric alarm system or defense mechanism. For example, the sensation of an insect crawling on the skin prompts an immediate reaction to brush it off, protecting the individual from potential harm.

Tickling also plays a crucial role in human psychological development and the creation of a sense of self. It serves as a form of preverbal communication and helps infants learn the boundaries between “self” and “other,” especially since it is neurologically impossible for a person to tickle themselves. This interaction fosters intimacy through a concept known as “benign and playful aggression,” where the tickling is perceived as a mock attack or a caress in a mildly aggressive disguise,. Consequently, tickling is viewed as a momentous entry point into the universe of pretense and fiction, allowing the brain to process a simulated threat as a source of social bonding

Tickle torture during history

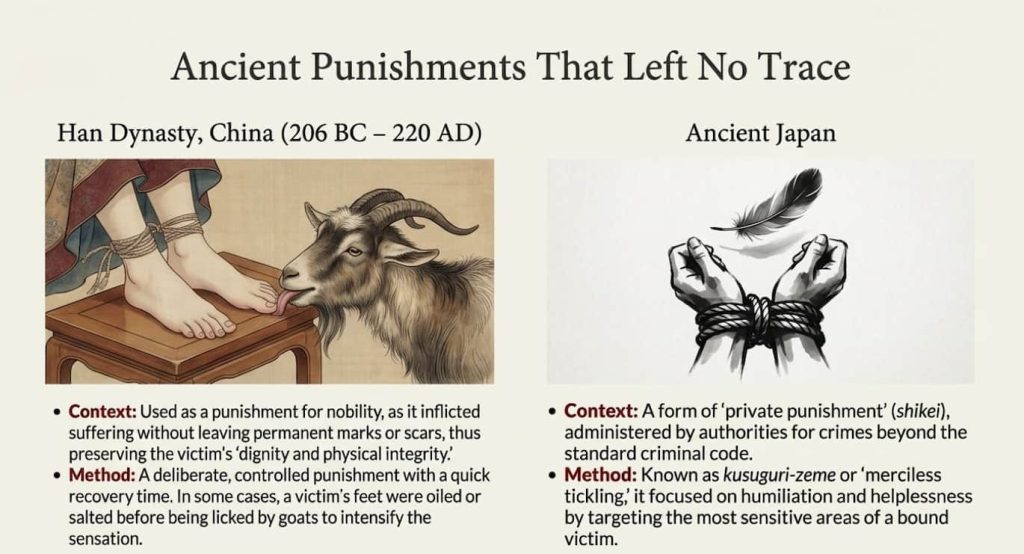

Ancient China

In Ancient China, particularly during the Han Dynasty, tickle torture was a preferred method for punishing individuals of noble status. This practice was highly valued by the state because it inflicted no lasting physical harm and left no permanent marks, allowing the nobility to suffer for their crimes while retaining their public dignity and physical integrity.

Historical accounts, such as those found in the text “The Art of Punishment and Torture,” suggest that the quick recovery time associated with tickling made it an ideal tool for disciplining the elite without the unsightly consequences of more violent methods.

By targeting the body’s involuntary reflexes, the Han authorities could induce a state of sensory overload and submission that was psychologically devastating yet physically invisible. This ensured that the social standing of the punished noble was preserved in the eyes of the public, even as they endured intense physiological distress and humiliation.

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, historical records and hieroglyphic evidence suggest that tickling was utilized as a specialized interrogative tool to extract secrets or confessions. This application of tickle torture was designed to be both a physical and psychological ordeal, targeting the most vulnerable areas of restrained victims such as the feet, ribs, and underarms.

The Egyptians, known for their ingenuity, often applied oils to the skin to heighten sensory sensitivity before the torture began, ensuring that every touch was magnified. This method relied on creating a debilitating cycle of uncontrollable laughter, physical discomfort, and eventual total exhaustion to break the victim’s resolve. By immobilizing the subject, interrogators were able to turn a reflexive bodily response into a potent weapon of coercion and control.

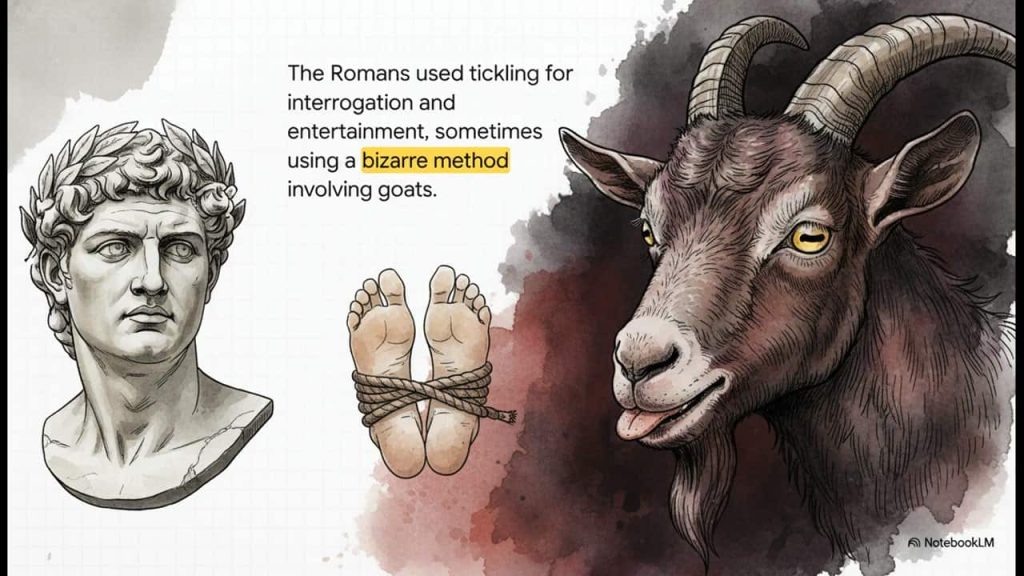

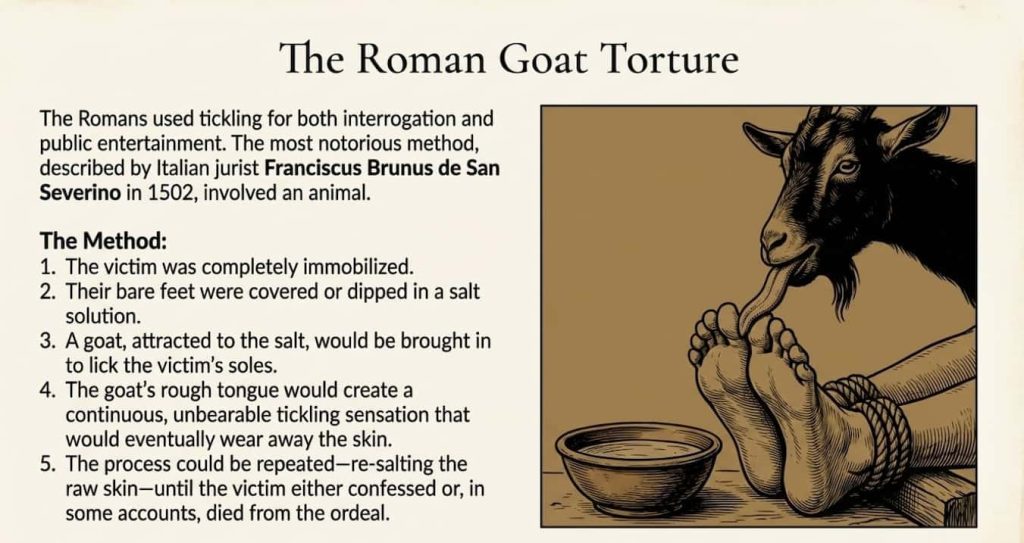

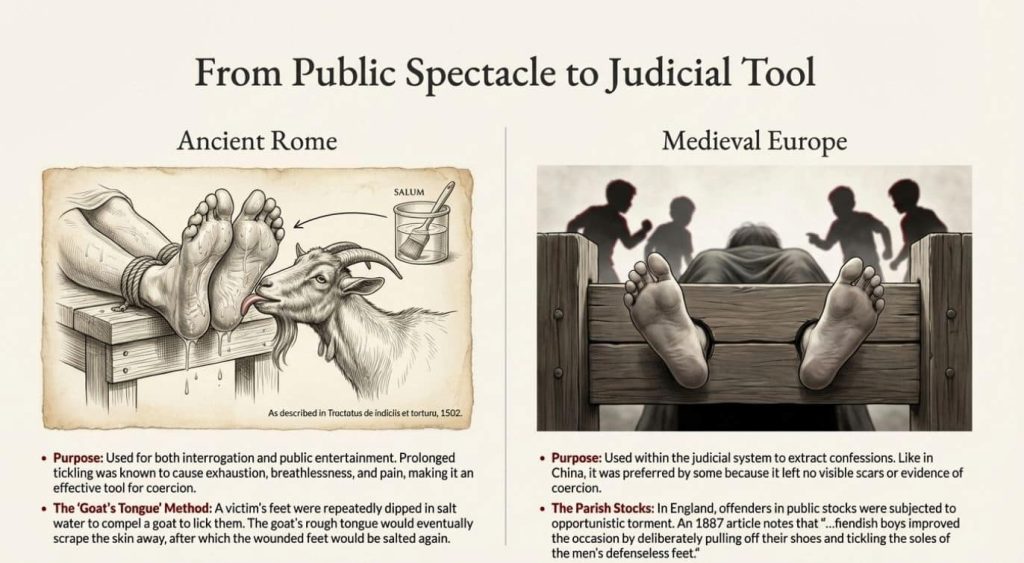

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire utilized tickle torture for both interrogation and public entertainment, often subjecting restrained prisoners or slaves to relentless stimulation for the amusement of an audience. A particularly brutal and creative method described in the 1502 treatise Tractatus de indiciis et tortura by the Italian jurist and monk Franciscus Brunus de San Severino involved the strategic use of animals.

A victim’s feet would be dipped in salt water or a brine solution, after which a goat would be brought in tolick the salt off. While the goat’s rough tongue would initially cause unbearable and frantic tickling, the process became increasingly lethal as the tongue’s abrasive surface gradually rasped away the skin. As the wounded skin was repeatedly covered with more biting salt solution and licked again, the sensation transitioned from a panic-induced laughter into excruciating pain.

Some historical accounts, such as those discussed by physiologist Joost Meerloo, suggest that this process could be continued ad infinitum until the victim eventually died from the sustained torture.

Ancient Japan

In Ancient Japan, the practice of kusuguri-zeme, which translates literally to “merciless tickling,” was a recognized component of a punitive system known as shikei. This system involved “private punishments” administered by those in authority for various offenses that frequently fell outside the boundaries of the formal criminal code. During these sessions, victims were typically bound and immobilized, allowing their tormentors to focus intensely on their most sensitive areas, such as the underarms and the soles of the feet.

The deliberate application of this method was designed to overpower the victim’s physical will and induce a profound state of humiliation and helplessness. Although historical documentation of this practice is less extensive than other methods, its effectiveness as a psychological weapon remained a point of interest for centuries.

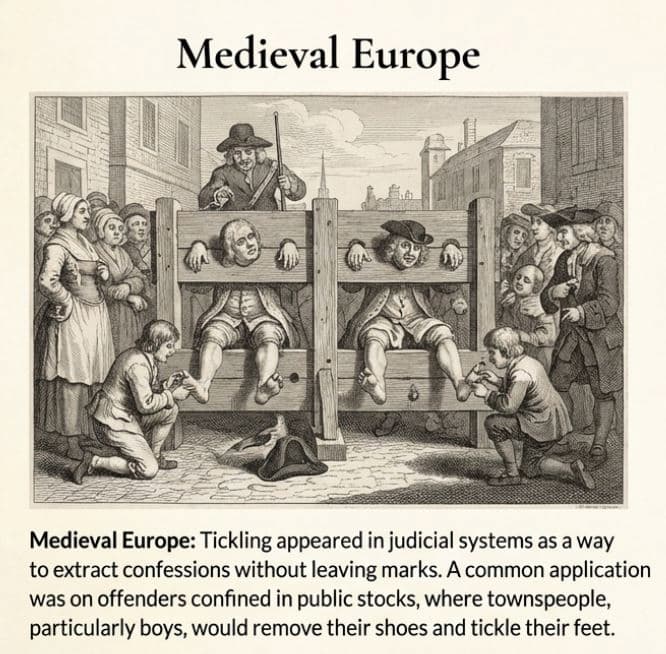

Medieval and Early Modern Europe

During the Middle Ages and the early modern period, tickle torture occasionally emerged within European judicial systems as a strategic method for extracting confessions. Because tickling targets the body’s nerve endings to trigger involuntary responses without causing permanent physical trauma, it left no visible scars or injuries that could be used as legal evidence of coercion. In England, this form of torment was often utilized as a secondary or informal harassment for individuals already held in the parish stocks for public morality offenses.

According to the 1887 article “England in Old Times,” local “fiendish” boys would often “improve the occasion” by removing the shoes of these defenseless offenders to tickle their bare soles as a form of communal humiliation.

Beyond its punitive use, this era saw philosophers like René Descartes analyze tickling as a complex sensory experience where the soul feels the body’s “titillation” through rhythmic nervous stimulation. This philosophical perspective highlighted that tickling sits on a precarious edge, where the pleasure of the stimulation can easily tip into the agony of torture if the nerves lack the strength to resist the violent action.

The 19th Century

By the Victorian era, accounts of tickle torture began to emerge in the context of domestic abuse and literary fiction. An 1869 report in the Illustrated Police News detailed a harrowing case where a man named Michael Puckridge tied his wife to a plank under the guise of treating her varicose veins, only to tickle her feet until she reportedly lost her sanity.

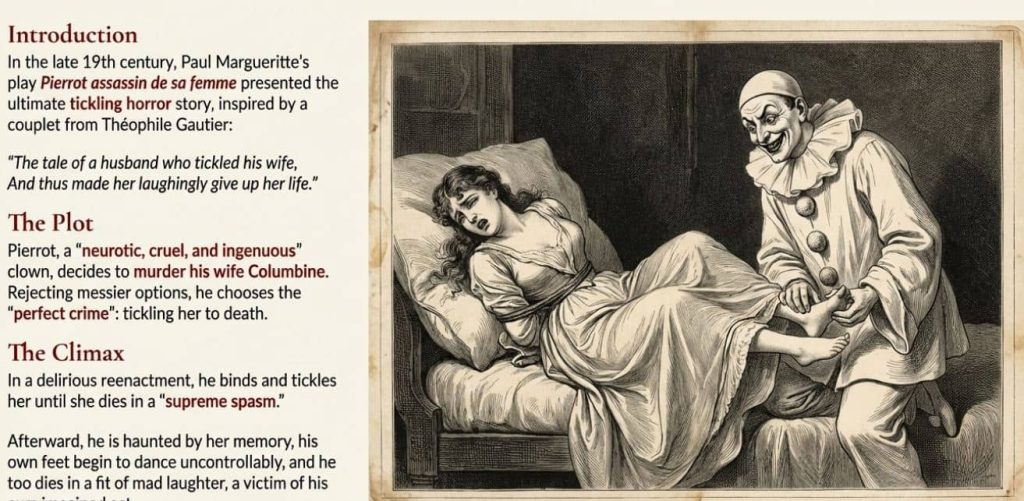

This era also saw the theme enter popular culture through the pantomime character Pierrot. In the 1882 play Pierrot assassin de sa femme by Paul Margueritte, the protagonist decides to murder his wife by tickling her to death, viewing it as a “perfect crime” because it leaves no marks and causes the victim to expire in a “supreme spasm” of forced laughter.

The 20th Century

Tickle torture took a dark turn during the major conflicts of the 20th century.

In Nazi concentration camps like Flossenbürg and Sachsenhausen, guards used tickling as a psychological and physical tool of abuse. In his memoir The Men with the Pink Triangle, survivor Heinz Heger described witnessing an SS sergeant tickle a naked prisoner with goose feathers. The victim’s forced laughter eventually turned into cries of pain and uncontrollable sobbing as he twisted against his chains.

In the 1950s, the Jesuit priest Tomas Rostwarowski documented that communist Polish security forces used tickling during the interrogation of prisoners. Witnesses reported hearing the constant, agonizing laughter of a woman being tortured in this manner for days and nights on end.

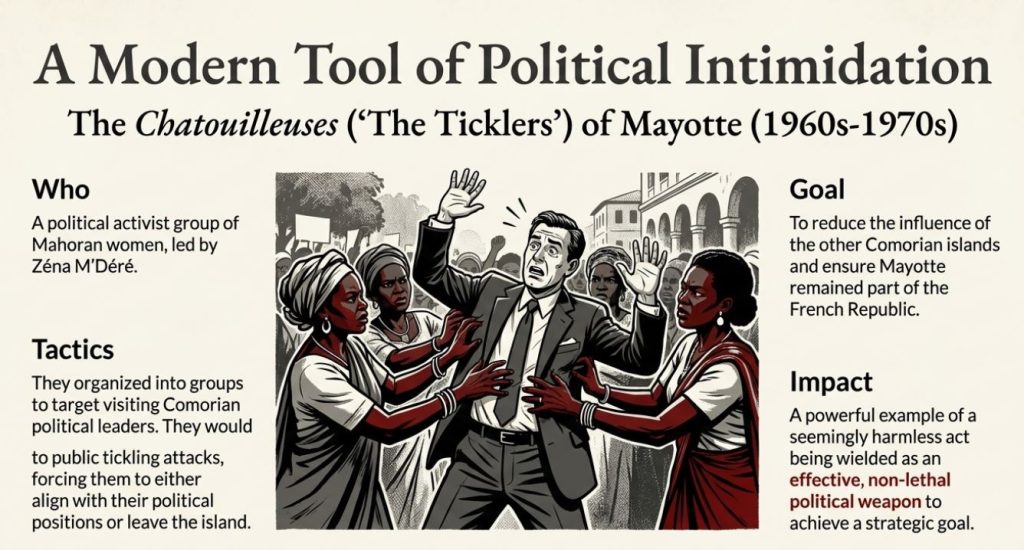

Furthermore, in the 1960s and 70s, a group of female activists in Mayotte known as the Chatouilleuses (The Ticklers) used this method for political intimidation. They would target Comorian political leaders, subjecting them to tickling to force them to align with their political positions or leave the island.