Scientific American Frontiers was an American documentary television series that aired on PBS from October 1, 1990, to April 13, 2005. It served as a companion program to the Scientific American magazine and focused on new technology, discoveries in science and medicine, and cutting-edge scientific developments.

Leggi tutto: Tickling Study #6: “Scientific American Frontiers”The show was produced by the Chedd-Angier Production Company. It initially featured MIT professor Woodie Flowers as the host until 1993, after which actor Alan Alda became the permanent host, continuing until the show’s end in 2005. During its run, the program typically aired new episodes every two to four weeks.

Episode 5, season 11, was focused on tickling, titled “Life’s Little Questions II.” This episode examined questions such as why people cannot tickle themselves, why scientists cannot cure the common cold, and why peppers are hot. The segment on tickling addressed the science and curiosity behind the sensation of tickling and why it provokes laughter and reactions in people.

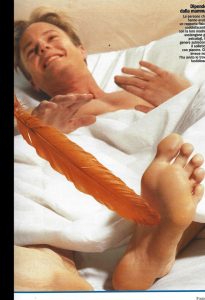

Alan Alda finds himself taking part in an experiment that is as curious as it is entertaining. Psychologist Christine Harris wants to answer a deceptively simple question: why can’t we tickle ourselves?

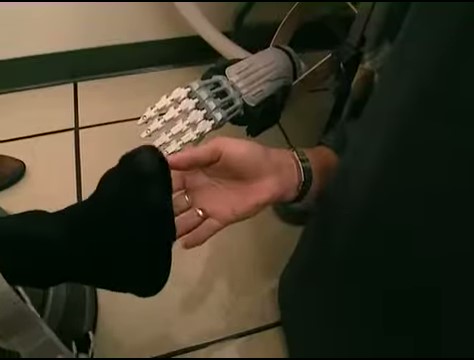

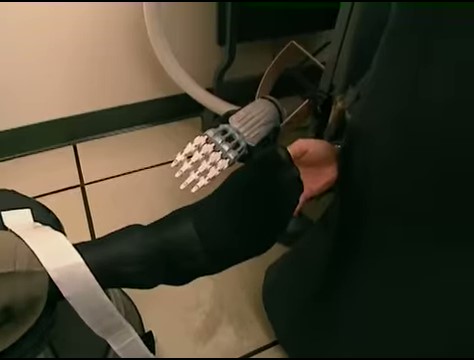

Christine Harris welcomes Alan with a smile and lays out the rules of the game: he’ll be tickled twice, first by her and then by a machine. To isolate the sensation, Alan has to wear a blindfold and earplugs, while one foot is strapped down to face the so-called “tickle machine.”

Alan agrees, but with a hint of suspicion. As Christine straps his foot in, he remarks that it could be a little tighter. Then the moment of truth arrives. Christine presses a button and, after a few seconds, Alan bursts out laughing:

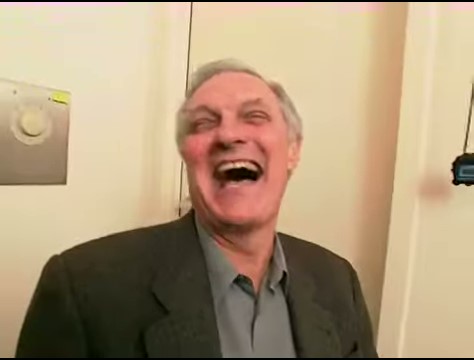

“Was that the machine?” he asks in disbelief.

“Yes, that was the machine,” she replies matter-of-factly.

When asked to rate the tickling, Alan doesn’t hesitate: a full seven out of seven. Then it’s Christine’s turn to do the tickling directly. Alan laughs again, but this time the score drops: “Maybe five and a half, six at most. Sorry to say… you’re a nice person, but the machine was more aggressive.”

Christine removes the blindfold and earplugs, asking Alan to describe the difference. Alan explains that the “machine” felt relentless, almost as if it was digging inside his foot and wouldn’t quit, whereas Christine’s tickling was “more courteous.”

Time for the big reveal. Christine shows Alan the “machine,” a collection of lights and old sensors cobbled together: pure fakery. In reality, the supposed machine tickling was done by an assistant hidden under the table. Alan bursts into laughter: “It’s a complete fraud!”

“We like to call it a mock tickle machine. Mock sounds better than fraud,” Christine counters.

Behind the trick lies a precise hypothesis: in order to laugh, the brain has to believe the tickling comes from someone else. If a person thinks a machine is doing the tickling, they should still laugh. And that’s exactly what the experiment confirms — belief alone is enough to trigger the response.

Alan points out a flaw: they haven’t actually tested a real machine, only the belief in one. Christine admits that building a genuine tickling device would be complicated, but in London, neuroscientist Sarah Blakemore has already managed it.

Sarah’s robot tickles the palm of the hand, and the sensation changes depending on who’s in control. When participants move the robot themselves, the ticklish feeling disappears. But if a small delay is introduced between their action and the robot’s response, the tickling returns. The brain anticipates the outcome of its own movements and dampens the response, which is why we can’t tickle ourselves.

To explore whether ticklish laughter is similar to humor-induced laughter, Christine designs another experiment. She shows participants a funny video to “warm them up” with laughter, then tickles them right after. The idea is that being in a good mood should amplify the tickle response. But the results say otherwise: there is no warm-up effect. Ticklish laughter and humorous laughter don’t seem to be the same, and they don’t influence each other.

That leaves the final question: what is tickling for? Christine suggests it may have evolved as a way to develop combat or play skills. Children chasing and tickling each other are practicing how to react, twist, and escape. The laughter, even if misleading, encourages the tickler to keep going, turning the interaction into a natural training ground.

Ironically, many people don’t actually enjoy being tickled. Christine admits it without hesitation: “No, I don’t like it. Not at all.” Alan can’t help but laugh again: “You don’t even like talking about it!”