Focus is an Italian monthly popular science magazine published in Milan, Italy, since 1992. It covers a wide range of topics including science, technology, history, health, and social issues, often accompanied by attractive pictures and illustrations. Besides the main magazine, Focus has given rise to spin-offs like Focus Extra, Focus Storia, Focus Junior, Focus Pico, and Focus Wild, targeting various audiences including children and history enthusiasts.

Leggi tutto: Tickling study #4: Focus (magazine)Focus aims to “discover and understand the world” and features articles that make scientific and cultural topics accessible and engaging. It also includes interactive elements such as reader contributions. The magazine has a strong circulation history, having reached over 600,000 copies sold at its peak and continues to be influential in the Italian science communication landscape.

Over the years, Focus has published several articles, print and online, related to tickling, reporting and explaining studies done on these phenomena.

Among the most important blog posts:

The article discusses the scientific research behind why people cannot tickle themselves, a question that has intrigued thinkers since ancient Greece. It highlights serious cognitive psychology and evolutionary science studies, especially those by Michael Brecht at Humboldt University of Berlin.

Brecht conducted experiments with pairs of volunteers who were already physically comfortable with each other. One person would tickle the other while researchers recorded reactions with high-definition cameras. The time to react to tickling on the face and breathing was about 300 milliseconds, followed by vocalizations after 200 milliseconds. This reaction time is longer than typical touch responses due to the emotional complexity of tickling.

In a second test, the volunteers also attempted to tickle themselves either on the same or opposite body part. The result was that self-tickling had no effect and even reduced the reaction to external tickling. Researchers believe this is because the brain cannot predict external touch locations but can anticipate self-touch, which cancels the tickling sensation. Brecht suggests this mechanism evolved to prevent constant laughter or discomfort from normal self-touch like scratching or movement.

Charles Darwin suggested that to enjoy tickling, one needs to be in the right mood. Researchers at Humboldt University in Berlin tested this theory using rats, which also exhibit a form of laughter through ultrasonic vocalizations. The researchers tickled rats and observed their joyful reactions, such as jumping and vocalizing, indicating that tickling is pleasurable for animals as well.

By measuring neural activity in the rats’ somatosensory cortex—the brain region where touch is processed—they found increased neuron firing during tickling. Remarkably, stimulating this brain area directly induced the same laughter-like behaviors in rats, confirming its role in generating tickling sensations.

However, rat responses to tickling diminished significantly when they were anxious, for example, when placed in unfamiliar situations. This shows that negative emotions can inhibit the tickling sensation in the brain.

The study highlights tickling as an ancient form of physical social interaction tied to play and positive emotions, and emphasizes how mood profoundly affects the experience of tickling.

Focus Extra n.18

The area most sensitive to the stimulus of tickling is the armpits. This was proven at the University of San Diego, USA, by measuring the duration of laughter caused by tickling various areas of the body.

The body’s areas were consequently divided into “not very sensitive” (palms of the hands and neck), “moderately sensitive” (throat, ribs, knees, feet), and “very sensitive” (sides and armpits). On average, tickling under the armpits triggers a laugh of 2.6 seconds, while on the palms it’s just 0.4 seconds

Tactile stimulation can have different intensities, such as with tickling. A very slight stimulation, like a tarantula walking on the chest, is called “knismesis,” and it rarely induces laughter. You can even cause this kind of tickling yourself.

There is another type of tickling called “gargalesis,” which cannot be self-induced. It consists of a more decided pressure exerted by another person (or even a machine) on particular areas of the body, like the armpits, the palms of the hands and feet, the sides, and the neck. This type of tickling can often be unpleasant, but it is accompanied by bursts of laughter.

Why? The laughter is believed to encourage the “tickler” to continue; if the tickling produced a negative reaction, the activity would stop. It’s also thought that this stimulation, especially among mammal cubs, helps develop fighting skills.

So, why can’t we tickle ourselves? The most likely hypothesis is that the brain isn’t taken by surprise because it’s the one commanding the action.

Focus n.57 (1997)

What is tickling? Does it have to do with sex? Can even a robot do it? Science facing an enigma.

At the University of San Diego (USA), they even built a “tickler robot“. It was capable of tickling the feet of a group of volunteers by moving a feather with its mechanical arm. They discovered that people laugh hysterically even if a machine, not a human, is tickling them.

This is not surprising. Tickling is one of the most enigmatic phenomena involving the human body, and scientists had not been able to provide a comprehensive explanation for it until now. Today, however, thanks to studies like this and experimental research that has considered all its aspects, it seems the mystery of tickling has finally been revealed.

Since the time of Socrates, philosophers and scientists have been fascinated by tickling. In 1677, Francesco Bacon observed in his Natural History that “when they are tickled, men, even if in a sad state of mind, cannot help but laugh”. This is not the same type of laughter provoked by a joke, for example. Researchers from UCLA in San Diego, Cristin Harris and Nicholas Christenfeld, conducted an experiment to see how different it is.

“Normally,” explains Harris, “if you watch several cartoons one after another, the one that makes you laugh the most is the third, because it exploits the so-called ‘strengthening effect’ (a kind of predisposition) caused by watching the first two.” “Does laughter from tickling also undergo this effect? To understand this, we tried to tickle a group of volunteers: some after they had watched a comedy film, others after a boring documentary.” The result: there was no difference in their reactions. “They all laughed in the same way. Conclusion: the strengthening effect does not work with tickling.”

Another difference is that tickling has no effect on certain people. And the same person can burst out laughing or feel a sense of annoyance depending on the situation they are in. This is because tickling, it has been discovered, is a response from the body that occurs on multiple levels. It is partly a kind of conditioned reflex, like a leg that kicks when a doctor hits the knee with a hammer, and partly a phenomenon that has to do with the psyche.

From a physiological point of view, the mechanism is elementary. When a finger brushes the skin, some nerve endings are stimulated that transmit the signal to the brain, where the information is processed. This causes a nervous excitement that can turn into a laugh.

According to scientists’ research, there are at least two things that itching and tickling have in common: the sensors that transmit the sensations to the brain and the initial pleasure they cause. Unlike tickling, however, itching responds to a precise physiological need: to quell the sensation of irritation of the nerve fibers of the skin with a vigorous and repeated rubbing.

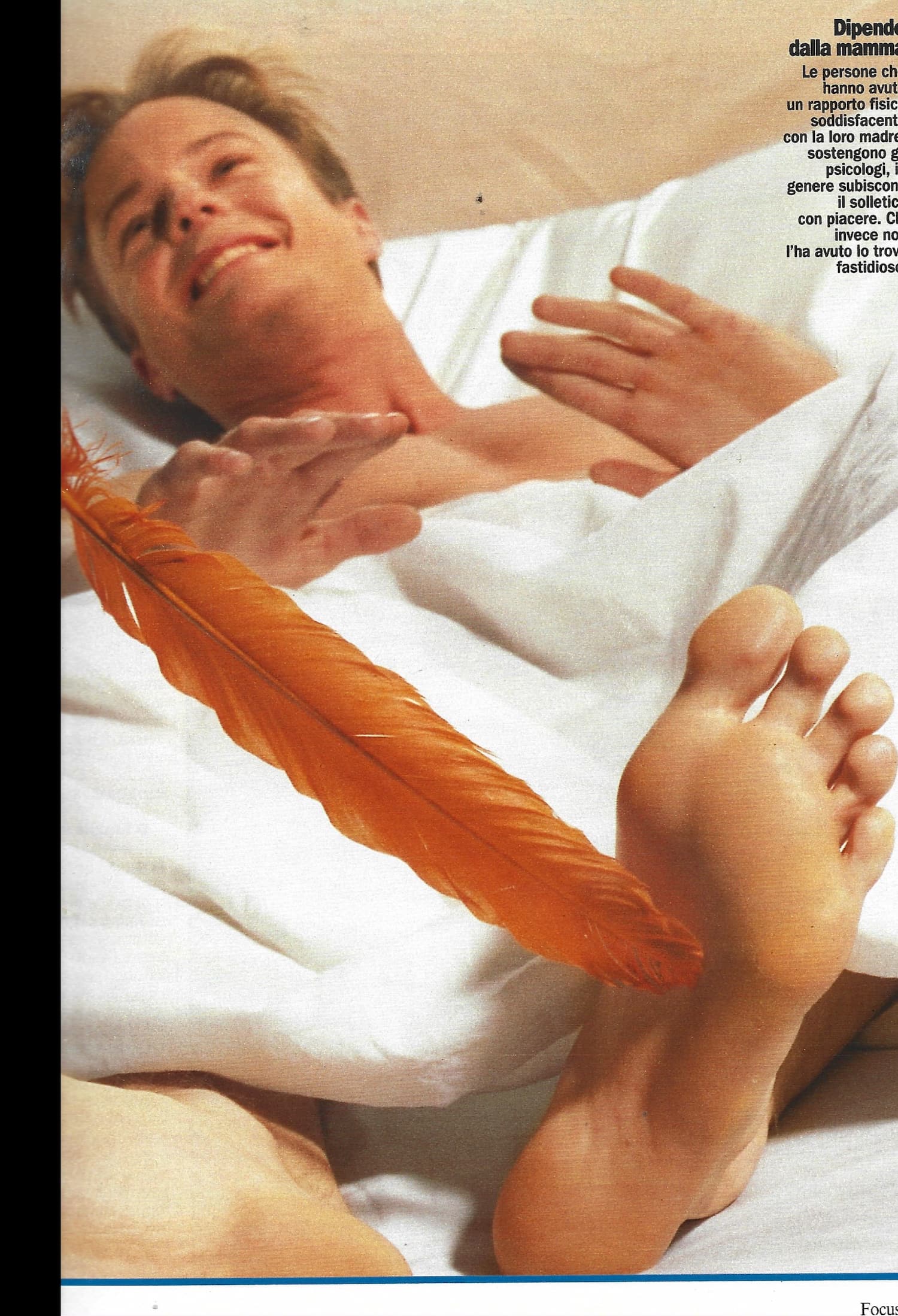

According to psychologists, people who have had a satisfying physical relationship with their mother generally enjoy being tickled. Those who haven’t had such a relationship find it annoying.

It’s ideal for tickling the feet. But it also works well on forearms, neck, and throat.

Excellent for what a physiologist, Houssay, classifies as “first-type tickling,” that is, light tickling on the cheeks and hands.

It has been shown that even a robot’s hand—using a pen—can make people laugh hysterically.

Generally, scientists have discovered, you start laughing more or less after 7 seconds and it continues for another 50. After that, the excitement decreases and tickling returns to what it is in reality: skin contact.

But you don’t always laugh: to turn the nervous impulse into a laugh, a psychological elaboration is needed. In other words, physical contact can be experienced as a pleasant experience or a threat. And it only makes you laugh when it has both these values.

“It seems that to feel tickling,” writes Charles Darwin, “one must not know the precise point that will be stimulated; a child cannot tickle himself.” The absence of threat and unpredictability, in fact, makes self-tickling impossible. The combination of the two key ingredients—pleasure and uneasiness—depends on personal experience. “The physical relationship one had with their mother matters,” says Vezio Ruggeri, a psychophysiologist at the University of Rome. “If it was positive, the pleasure component will prevail; if it was negative, the distressing one will prevail.”

In short, tickling is a reflex in which we tell a little about ourselves. This is why it is sometimes used in sexology to re-educate the body to contact with others. Brushing against each other, teasing, unleashing repressed hilarity is a first step to rediscovering eroticism.

The loss of control caused by tickling also has unpleasant effects. Children know this, as they often engage in “tickle wars,” where the goal is not to amuse the opponent but to make them lose control of their body. In our language, the verb to tickle (solleticare) appeared in the 15th century as an evolution of “leticare,” which means to fight. And in the history of torture, there is also a place for “death by tickling,” inflicted in Germany on some unfortunate people during the religious wars of the 17th century.